Baby Weight Gain Doubled in 2 Months Obese

Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the relationship betwixt nativity weight and rapid weight gain in infancy and markers of overweight/obesity in childhood, using dissimilar cutoff values for rapid weight gain.

Subjects/methods:

Cross-sectional report involving 98 5-year onetime pre-schoolhouse Brazilian children. Rapid weight gain was considered every bit weight gain in standard deviation score (SDS) above +0.67, +1 and +2 in relation to nascency weight, at any time during the first 2 years of life. The nutritional status of the children was determined by anthropometry and electrical bioimpedance. Multiple linear regression analysis was used, considering fat mass percentage, body mass index (BMI), waist and cervix circumferences as outcomes.

Results:

Nascency weight, rapid weight gain (assessed by different cutoff values) and maternal obesity were positively associated with increased fat mass percentage, BMI, waist and neck circumferences. Different cutoff values of rapid weight gain did non alter the positive associations betwixt rapid weight gain and fat mass percent (>+0.67 SDS, P=0.007; >+ane SDS, P=0.007; >+ii SDS, P=0.01), BMI (>+0.67 SDS, P=0.002; >+1 SDS, P=0.007; >+2 SDS, P<0.001), waist circumference (>+0.67 SDS, P=0.002; >+one SDS, P=0.002; >+two SDS, P<0.001) and neck circumference (>+0.67 SDS, P=0.01; >+one SDS, P=0.03; >+2 SDS, P<0.001).

Conclusions:

The utilise of different cutoff values for the definition of rapid weight proceeds did non interfere in the associations betwixt nascence weight and rapid weight gain with fat mass percentage, BMI, waist and neck circumferences. Children with the highest nativity weight, those who undergo rapid weight gain in infancy and whose mothers were obese, seemed to exist more at risk for overweight/obesity.

Introduction

Data published by the World Health Organization1 have shown a worrisome increase of overweight and obesity during the first years of life. In infancy, hyperplasia and/or hypertrophy of adipose cells results in an exacerbated expansion of adipose tissue, a characteristic of obesity, which tends to persist into machismo.ii This mechanism can be explained by the developmental origins of health and illness hypothesis, which suggests that an insult or stimulus during critical periods of development, such equally growth in the intrauterine period and infancy, has long-term effects on the physiology, structure and functions of the organism.iii, 4, five

Birth weight is a proxy of intrauterine growth and appears to be associated with body composition throughout an individual's life.half dozen, vii In add-on to birth weight, rapid weight gain has besides been associated with the incidence of obesity after in life.8, ix The greatest variation in rates of weight gain is seen in the first 1–ii years of life when infants may show significant rapid weight gain or 'take hold of-upwards' to compensate for intrauterine restraint.10

No standard definition of rapid weight gain exists in the international literature. In well-nigh studies, rapid weight proceeds in infancy is divers as an increase in weight >+0.67 standard deviation score (SDS) between birth and two years.xi, 12 However, other cutoff values for rapid weight gain take also been reported: >+1 SDS,13 >90th percentile14 and >ix 764 g.xv In a review comprising studies that used different cutoff values for rapid weight gain in infancy, Ong and Loos16 institute an association between rapid weight gain and subsequent obesity risk.

Body mass index (BMI), a parameter extensively employed in epidemiological studies, is more often than not used for the diagnosis of overweight and obesity in childhood.ane, 17 Neck circumference has been proposed equally a potential marker of childhood obesity. This marker shows an of import association with BMI, is a simple and rapid measure and specially useful in population studies.18 Waist circumference is a proxy of visceral fatty and is also an important marker of overweight/obesity and chronic diseases.xix, xx McCarthy et al. 21 suggested refinement of the diagnosis of overweight/obesity by the assessment of body composition and published reference curves of fatty mass percentage measured past bioelectrical impedance.

The early on detection of overweight and obesity during the first years of life permits the application of acceptable interventions to avoid obesity-related problems after in life. Therefore, the objective of the nowadays study was to evaluate the clan of nascence weight and rapid weight gain in infancy with markers of overweight and obesity in childhood using different cutoff values for rapid weight gain.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at all municipal schools in Capão Bonito city, Brazil, and included 5-year-old children enrolled in the first form of simple school. Children born prematurely and children with genetic and chronic diseases were excluded from the report.

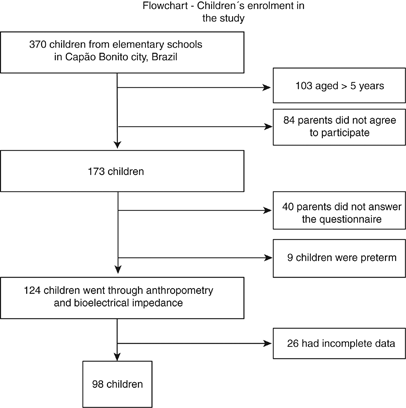

Birth weight and gestational age were obtained from the kid's hospital belch record and/or immunization card. Weight gain during the starting time 2 years of life was transcribed from the child'southward immunization carte or health service records. The flowchart in Figure 1 illustrates the different phases of the study.

Flowchart of children's enrollment.

The parents/legal guardians answered a full general questionnaire containing information near demographic, educational level, and obstetric variables, breastfeeding, family history of obesity (especially maternal obesity), and physical activity of the children.22

The anthropometric measurements were determined in indistinguishable, by the same pediatrician, according to Lohman et al. 23 Later on ten- to 12-h fast, the children were weighed on a portable electronic scale (model 7500, Soehnle, Murrhardt, Germany) to the nearest 100 g. Height was measured using a Leicester Portable Height measure (Seca, Hamburg, Frg) to the nearest 0.ane cm. Waist and neck circumferences were obtained with a tape measure (model 34103, Stanley, New Britain, CT, United states of america) to the nearest 0.1 cm. Waist circumference was classified co-ordinate to the National Health Statistics Written report,24 with values above the 85th percentile (58.viii cm for boys and lx.vi cm for girls) being divers as excess weight. Neck circumference was classified according to Nafiu et al.,18 with values above 28.5 and 27 cm for boys and girls, respectively, being defined as excess weight. The cutoff values for children anile half-dozen years or more than were used as no cutoff values are bachelor for five-yr-old children.

BMI was considered to be a marking of nutritional status using the WHO25 bend as a reference standard. Children with a BMI-for-age between 1 and two z-score from the hateful were classified as overweight and those with a BMI-for-age >ii z-score were classified as obese. In this study, rapid weight proceeds was divers equally weight gain >+0.67, +1 or +two SDS in relation to birth and a time indicate within the first 2 years of life, considering that there were at least 8 measurements from the children in this flow of life. Body composition was evaluated by bioelectrical impedance (MC-180MA, Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Body fat percentage was classified based on the values proposed past McCarthy et al. 21 using the 85th and 95th percentiles for age and gender as cutoff values for overweight and obesity, respectively.

The Stata ten for Windows software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was utilized for data assay. The variables are reported as absolute and relative frequencies and measures of central tendency (ways) and dispersion (standard deviation and range). Four multiple linear regression models were used, one for each dependent variable analyzed (fat mass percentage, BMI, waist circumference and neck circumference) and for the different definitions of rapid weight gain (above +0.67, +1 and +2 SDS). Birth weight and rapid weight gain were the independent variables of interest and were controlled for the child'southward gender, breastfeeding, physical activity and maternal variables (age at nascence of the child, obesity and education). Birth weight and rapid weight proceeds remained in the regression model irrespective of the P level. The other variables were kept in the model when P≤0.20. A level of significant of P<0.05 was adopted.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Schoolhouse of Public Health, University of São Paulo, Brazil. All parents/legal guardians agreed to the participation of their children past signing the costless informed consent form.

Results

All 370 children, anile v years, attending the elementary schools in Capão Bonito city, Brazil, were selected for the study. However, 187 were excluded considering 103 aged over 5 years at the time of information collection and 84 parents did not agree to participate. From the 173 remaining children, 40 parents did not respond the questionnaire and 6 children were born preterm. From the 124 remaining children, 26 had incomplete data on anthropometry and/or bioelectrical impedance (Flowchart). Therefore, the terminal sample consisted of 98 children.

There was no divergence in mean birth weight (3.4±0.5 and 3.3±0.five kg, respectively), maternal age at nascency of the child (25.ix±6.half dozen and 26±6.iv years) or maternal education (7.iv±3.ix and half-dozen.nine±4.1 years) betwixt the 124 and 98 children.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 98 children and their mothers; more of the children being girls (56.one%). But 3 (iii.1%) children had low birth weight (<2.5 kg) and near half of them (49%) weighed from 3.0 to 3.v kg at nascence. Rapid weight gain was observed in 61.2%, 51% and 21.iv% of the children, according to the following cutoff values >+0.67, >+1 and >+2 SDS, respectively. Body fat percentage was above the 85th percentile at 5 years of historic period in approximately 43% of the children, characterizing overfat (thirty.6%) or obesity (12.two%).21 According to the WHO25 BMI-for-age z-score, 14.iii% of the children presented overweight and nine.ane% obesity (9.1%). In relation to the waist circumference curve classification,24 17.3% of the children were above or equal the 85th percentile. Using cervix circumference every bit an indicator, 19.4% of the population was overweight/obese.18 The hateful duration of breastfeeding was xiii.v (±fourteen.1) months, with mothers reporting exclusive breastfeeding for 4.1 (±2.6) months. Using the questionnaire adapted from Bracco et al.,22 approximately 85% of the children were active. Among the mothers of children participating in the written report, 11.ii% were adolescents (<19 years) and 63.3% were betwixt 20 and 30 years of age. Approximately 17% of the mothers reported to exist obese, a finding confirmed past the primary researcher, and 64.iii% had 8 years or less of formal education.

Tables 2, iii, 4 show multiple linear regression models including fat mass pct, BMI, waist circumference and neck circumferences as outcomes, and using 3 cutoff values for rapid weight gain (above +0.67, +1 and +2 SDS). For all models, fatty mass percentage, BMI and waist circumference were associated with nascence weight, rapid weight gain in infancy and maternal obesity. Associations with birth weight, rapid weight proceeds and gender were observed for the model including cervix circumference as outcome.

At that place were inverse correlations between birth weight and rapid weight gain in infancy, varying from −0.35 to −0.32 (P<0.001), for the iii different cutoff points used for rapid weight proceeds.

Discussion

In this report, we investigated the association of nascence weight and rapid weight gain in infancy with markers of overweight and obesity (fat mass pct, BMI, waist circumference and cervix circumference) in childhood, using different cutoff values for rapid weight gain (above +0.67, +i and +2 SDS). Fatty mass percentage, BMI, waist circumference and neck circumference evaluated at 5 years of historic period were positively associated with birth weight and rapid weight gain in infancy, irrespective of the cutoff value used.

The literature regarding the association between birth weight and obesity later in life is controversial. There are reports involving very large samples showing that the association follows a U-shaped26 or J-shaped curve.27 Recently, studies suggested that elevated weight at nativity, and not depression nascency weight, is a risk cistron for obesity later in life.28, 29 In the nowadays study, birth weight was positively associated with overweight/obesity at 5 years of age, in understanding with the latest findings. The human relationship between higher birth weight and afterward obesity might exist explained by the developmental origins of health and illness hypothesis, which suggests that disturbances during critical windows of development (such as growth in the intrauterine catamenia and infancy) cause permanent metabolic, physiological and structural adaptations.thirty Studies have explored the mechanisms underlying these associations and possible explanations include an increase in the number and/or size of adipose cells or functional alterations in adipose tissue.31, 32 Long et al. 32 provided bear witness that the college nascence weight of fetuses of overfed ewes is due to an increase of adipose tissue caused past higher lipogenesis and increased transport of fatty acids to fetal adipocytes. The authors observed that average adipocyte diameter in renal fatty was greater in fetuses of overfed mothers when compared with those of mothers not overfed. These physiological alterations in adipose tissue seem to be permanent, demonstrating the influence of the perinatal period and higher nascence weight on subsequent obesity.

Although nascency weight is associated with obesity in later life, rapid weight gain in infancy has been suggested to be a more important factor for the development of obesity. In fact, in a contempo meta-analysis,33 the inclusion of infant weight gain from 0 to 1 year improved the prediction of childhood obesity when compared with a model that independent only maternal BMI, birth weight and gender. The authors observed that the influence of weight gain in infancy on later obesity was significant over a wide range of birth weights. In a model adjusted for birth weight, gender and age, the adventure of childhood obesity doubled for each weight increase of 1 SDS between 0 and 1 year (odds ratio=i.97). This increment in the gamble of babyhood obesity was even higher for each increase of one SDS betwixt 0 and 2 years. These findings suggest that, like birth weight, rapid weight proceeds also alters the physiology of adipose tissue and fat-free tissue.

In this study, rapid weight proceeds (independently of the cutoff values used) showed an inverse association with nascency weight. This suggests that information technology could be 'catch-up',10 fifty-fifty in those infants born inside the normal birth weight range.

In agreement with the conclusion of Ong and Loos,16 different cutoff values did not seem to interfere with the presence of overweight and obesity afterward in life. The overall prevalence of rapid weight gain or 'catch-upwards' observed in our study (61.seven%) at the cutoff >+0.67 SDS was college than that reported by Ong et al. 10 (30.7%), in a study involving 260 British infants. In a retrospective accomplice study of adolescents, Monteiro et al. 34 observed a prevalence of rapid weight gain in infancy, defined as >+1 SDS and >+ii SDS, of xi% and 4.2%, respectively. The possible explanations for the differences between these 3 studies are: (ane) socioeconomic condition and (2) differences in the definition of rapid weight gain. The nowadays study was conducted in one of the near underprivileged regions of the State of São Paulo (Human Development Index 0.663)35 different from the studies of Monteiro et al. 34 in Pelotas city, State of Rio Grande do Sul (Human Development Index: 0.768)35 and the ALSPAC study,ten which involved a population in Bristol urban center, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. Furthermore, Ong et al. x and Monteiro et al. 34 defined rapid weight proceeds equally the divergence between weight (SDS) at 2 years of age and birth weight (SDS) above +0.67. In the present written report, rapid weight gain was defined as the deviation betwixt weight (SDS) >+0.67, >+1 and >+2 at any fourth dimension during the first 2 years of life and birth weight (SDS), considering that the anthropometric information were determined at least eight times during infancy.

Both nascency weight and take hold of-up growth had an impact on markers of overweight/obesity (fat mass percentage, BMI, waist circumference and neck circumference). The prevalence of overweight/obesity varied co-ordinate to the mark used. Using BMI, 23.4% of the children were diagnosed as overweight/obese at 5 years of age, whereas almost the double (42.8%) was diagnosed equally overfat/obese according to fat mass percentage. BMI has been used over many years as a parameter for the diagnosis of overweight and obesity. However, this parameter does not provide information almost the body composition of a bailiwick and is therefore considered to be a poor marker of obesity,13, 36 although it is still used in epidemiological studies.37, 38 Some investigators prefer the use of fat mass percentage as a marker of overweight/obesity13 and nosotros found this marking to exist more sensitive for this diagnosis.

Fatty mass percentage or BMI does non indicate the distribution of excess body adiposity. On the other manus, waist circumference is a valuable mensurate as it reflects central adiposity. The latter has been suggested to be associated with metabolic diseasesnineteen, 39 and, when evaluated in childhood, is an indicator of metabolic risks.20, forty In the present study, waist circumference was positively associated with birth weight and rapid weight gain, in understanding with other studies demonstrating that children undergoing rapid weight gain tend to accumulate excess adipose tissue in the central region.10

Cervix circumference showed a positive association with fat mass percentage, BMI and waist circumference. Every bit information technology is a practical and inexpensive measure, neck circumference tin be used for the diagnosis of overweight and obesity when BMI data are not available.18, 41, 42 The prevalence of overweight/obesity (19.4%) based on neck circumference measurement might exist underestimated, as the reference values available refer to American children anile 6 years or older.eighteen

Maternal obesity was another factor that showed a significant association with childhood overweight/obesity. Moaraeus et al. 43 and Lazzeri et al. 44 observed a strong association betwixt parental obesity and obesity in children aged seven–nine years and viii–9 years, respectively. Plain to be able to target children with the highest hazard of overweight and obesity, it is important to monitor family weight status whenever possible.

Duration of breastfeeding, concrete activity and educational level were not associated with the outcomes at 5 years of age. Breastfeeding has been reported to be a protective factor against overweight and obesity.45, 46 The lack of an association between breastfeeding and obesity might be due to memory bias, every bit we conducted a retrospective study in which exposure occurred 3–5 years before the interview. Withal, similar to our results, other investigators did not find an association between duration of breastfeeding and obesity.47, 48 Physical activity was probably non associated with overweight/obesity because of the difficulty in measuring this variable in a cross-sectional study involving children.x, 49 Parental pedagogy has been reported to be an important factor associated with childhood obesity. Gonzalez et al. fifty observed that parental education was associated with lower BMI in early adulthood. Keane et al.,51 however, referred a positive relationship between higher maternal educational level and BMI at age 9 years. The lack of association between maternal education and obesity observed in the present study might exist due to the homogeneity of our population. The children were selected from public schools in Capão Bonito city, an underprivileged region in the State of São Paulo, with low level of pedagogy.

Decision

The results of this study demonstrate that infancy is a disquisitional period for the development of overweight and obesity in later life, as confirmed by the associations of nascence weight and rapid weight gain with fat mass per centum, BMI, waist circumference and neck circumference at v years of historic period. The use of different cutoff values for the definition of rapid weight gain did not modify the associations observed between the variables and outcomes investigated. Children with the highest birth weight, those who undergo rapid weight proceeds in infancy and whose mothers were obese, seemed to be more at risk for overweight/obesity.

References

-

Onis Grand, Blössner M, Borghi Eastward . Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity amid preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 1257–1264.

-

Freedman DS, Sherry B . The validity of BMI equally an indicator of body fatness and chance among children. Pediatrics 2009; 124 (Suppl 1), S23–S34.

-

Mostyn A, Symonds ME . Early on programming of adipose tissue part: a big-brute perspective. Proc Nutr Soc 2009; 68: 393–400.

-

Lemos JO, Rondo PH, Pereira JA, Oliveira RG, Freire MB, Sonsin PB . The human relationship between birth weight and insulin resistance in childhood. Br J Nutr 2010; 103: 386–392.

-

Langley-Evans SC . Fetal programming of CVD and renal disease: creature models and mechanistic considerations. Proc Nutr Soc 2013; 72: 1–nine.

-

Globe Health System. Promoting Optimal Fetal Development: Study of a Technical Consultation. Globe Health Organization: Geneva, 2006.

-

Wells JC . The programming effects of early on growth. Early Hum Dev 2007; 83: 743–748.

-

Ekelund U, Ong Grand, Linne Y, Neovius 1000, Brage Southward, Dunger DB et al. Upward weight percentile crossing in infancy and early childhood independently predicts fatty mass in young adults: the Stockholm Weight Development Study (SWEDES). Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 324–330.

-

Oyama M, Saito T, Nakamura Thousand . Rapid weight gain in early on infancy is associated with adult body fat percentage in young women. Environ Health Prev Med 2010; 15: 381–385.

-

Ong KK, Ahmed ML, Emmett PM, Preece MA, Dunger DB . Association between postnatal catch-up growth and obesity in childhood: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000; 320: 967–971.

-

Mihrshahi S, Battistutta D, Magarey A, Daniels LA . Determinants of rapid weight gain during infancy: baseline results from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 2011; 11: 99.

-

Batisse-Lignier K, Rousset Southward, Labbe A, Boirie Y . Growth velocity in infancy influences resting energy expenditure in 12-14 year-erstwhile obese adolescents. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 625–629.

-

Stettler N, Kumanyika SK, Katz SH, Zemel BS, Stallings VA . Rapid weight gain during infancy and obesity in immature adulthood in a accomplice of African Americans. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77: 1374–1378.

-

Mellbin T, Vuille JC . Human relationship of weight gain in infancy to subcutaneous fatty and relative weight at ten 1/2 years of age. Br J Prev Soc Med 1976; 30: 239–243.

-

Toschke AM, Grote V, Koletzko B, von Kries R . Identifying children at high risk for overweight at school entry by weight gain during the first 2 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158: 449–452.

-

Ong KK, Loos RJ . Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: systematic reviews and hopeful suggestions. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95: 904–908.

-

Reilly JJ, Wilson ML, Summerbell CD, Wilson DC . Obesity: diagnosis, prevention, and handling; show based answers to common questions. Arch Dis Child 2002; 86: 392–394.

-

Nafiu OO, Shush C, Lee J, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Tremper KK . Neck circumference as a screening measure for identifying children with high torso mass index. Pediatrics 2010; 126: e306–e310.

-

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R . Waist circumference and not body mass alphabetize explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 379–384.

-

Eyzaguirre F, Mericq V . Insulin resistance markers in children. Horm Res 2009; 71: 65–74.

-

McCarthy Hd, Cole TJ, Fry T, Jebb SA, Prentice AM . Body fat reference curves for children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006; thirty: 598–602.

-

Bracco MM, Colugnati FA, Pratt Chiliad, Taddei JA . Multivariate hierarchical model for physical inactivity among public school children. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2006; 82: 302–307.

-

Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R . Anthropometric Standardization Reference Transmission. Man Kinetics Books: Champaign, IL, 1988.

-

McDowell MA, Fryar CD, Ogden CL . Anthropometric reference information for children and adults: The states, 1988-1994. Vital Health Stat 11 2009; 249: 1–68.

-

World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Historic period, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. World Wellness Organization: Geneva, 2006.

-

Newby PK, Dickman Pw, Adami HO, Wolk A . Early on anthropometric measures and reproductive factors as predictors of torso mass index and obesity among older women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29: 1084–1092.

-

Parsons TJ, Power C, Estate O . Fetal and early life growth and trunk mass index from nativity to early adulthood in 1958 British accomplice: longitudinal study. BMJ 2001; 323: 1331–1335.

-

Yu ZB, Han SP, Zhu GZ, Zhu C, Wang XJ, Cao XG et al. Nascency weight and subsequent risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2011; 12: 525–542.

-

Zhao Y, Wang SF, Mu M, Sheng J . Birth weight and overweight/obesity in adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr 2012; 171: 1737–1746.

-

Barker DJP . Mothers, Babies, and Health in Later Life 2nd edn, Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh; New York, 1998.

-

Budge H, Gnanalingham MG, Gardner DS, Mostyn A, Stephenson T, Symonds ME . Maternal nutritional programming of fetal adipose tissue development: long-term consequences for subsequently obesity. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2005; 75: 193–199.

-

Long NM, Dominion DC, Zhu MJ, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP . Maternal obesity upregulates fat acid and glucose transporters and increases expression of enzymes mediating fatty acrid biosynthesis in fetal adipose tissue depots. J Anim Sci 2012; 90: 2201–2210.

-

Druet C, Stettler Northward, Precipitous South, Simmons RK, Cooper C, Smith GD et al. Prediction of babyhood obesity by infancy weight proceeds: an individual-level meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012; 26: 19–26.

-

Monteiro PO, Victora CG, Barros FC, Monteiro LM . Birth size, early childhood growth, and adolescent obesity in a Brazilian birth cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 1274–1282.

-

PNUD – Programa das Nações Unidas para o desenvolvimento 2003. Ranking practice IDH dos Municípios practise Brasil 2003. Available at http://www.pnud.org.br/atlas/ranking/IDH_Municipios_Brasil_2000.aspx?indiceAccordion=ane&li=li_Ranking2003.

-

Prentice AM, Jebb SA . Beyond body mass index. Obes Rev 2001; ii: 141–147.

-

Badr HE, Shah NM, Shah MA . Obesity among Kuwaitis aged 50 years or older: prevalence, correlates and comorbidities. Gerontologist 2012; 53: 555–566.

-

Nikpartow N, Danyliw AD, Whiting SJ, Lim H, Vatanparast H . Fruit drink consumption is associated with overweight and obesity in Canadian women. Can J Public Wellness 2012; 103: 178–182.

-

Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S . Waist-to-summit ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2012; 13: 275–286.

-

Ibanez L, Suarez L, Lopez-Bermejo A, Diaz Thou, Valls C, de Zegher F . Early development of visceral fatty backlog afterward spontaneous catch-up growth in children with low birth weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 925–928.

-

Androutsos O, Grammatikaki E, Moschonis M, Roma-Giannikou Due east, Chrousos GP, Manios Y et al. Cervix circumference: a useful screening tool of cardiovascular hazard in children. Pediatr Obes 2012; 7: 187–195.

-

Hingorjo MR, Qureshi MA, Mehdi A . Neck circumference every bit a useful marker of obesity: a comparison with body mass alphabetize and waist circumference. J Pak Med Assoc 2012; 62: 36–40.

-

Moraeus L, Lissner L, Yngve A, Poortvliet Eastward, Al-Ansari U, Sjoberg A . Multi-level influences on childhood obesity in Sweden: societal factors, parental determinants and child's lifestyle. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 969–976.

-

Lazzeri G, Pammolli A, Pilato V, Giacchi MV . Relationship betwixt 8/9-yr-old schoolhouse children BMI, parents' BMI and educational level: a cross sectional survey. Nutr J 2011; ten: 76.

-

Hunsberger Thou, Lanfer A, Reeske A, Veidebaum T, Russo P, Hadjigeorgiou C et al. Infant feeding practices and prevalence of obesity in eight European countries - the IDEFICS study. Public Wellness Nutr 2012; 16: ane–ix.

-

McCrory C, Layte R . Breastfeeding and take a chance of overweight and obesity at nine-years of age. Soc Sci Med 2012; 75: 323–330.

-

Andersen LG, Holst C, Michaelsen KF, Baker JL, Sorensen TI . Weight and weight gain during early infancy predict babyhood obesity: a case-cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 1306–1311.

-

Dubois L, Girard Yard . Early on determinants of overweight at iv.5 years in a population-based longitudinal report. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006; 30: 610–617.

-

Pate RR, O'Neill JR, Mitchell J . Measurement of physical activity in preschool children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010; 42: 508–512.

-

Gonzalez A, Boyle MH, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Atkinson LR, Macmillan HL . Childhood and family influences on body mass index in early adulthood: findings from the Ontario Child Wellness Report. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 755.

-

Keane Eastward, Layte R, Harrington J, Kearney PM, Perry IJ . Measured parental weight status and familial socio-economical condition correlates with childhood overweight and obesity at age 9. PLoS One 2012; 7: e43503.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo-FAPESP (grant number: 2009/50767-0). Nosotros are grateful for the participation and support of the children and families of Capão Bonito city, São Paulo, Brazil. Nosotros also are indebted to the expert assist of our enquiry assistants.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of involvement.

Additional information

Author contributions

MRS designed the report protocol, collected information, participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the paper. NPdeC and VLVE participated in the statistical assay and estimation of data, and writing of the paper. JMS participated in the statistical analysis, estimation of data and writing of the paper. PHCR secured funding, designed the written report protocol, participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sacco, Thousand., de Castro, Due north., Euclydes, V. et al. Birth weight, rapid weight gain in infancy and markers of overweight and obesity in babyhood. Eur J Clin Nutr 67, 1147–1153 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.183

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.183

Keywords

- nativity weight

- rapid weight gain

- obesity

- fetal development

- fatty mass

Further reading

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/ejcn2013183

0 Response to "Baby Weight Gain Doubled in 2 Months Obese"

Post a Comment